gravis (gMG) affects many aspects

of patients’ lives

96% (n=27/28)

experience impacts

on their social life2

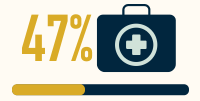

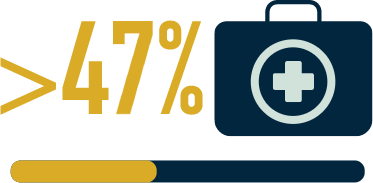

(n=36) have experienced

at least one major

depressive episode

within their lifetime3

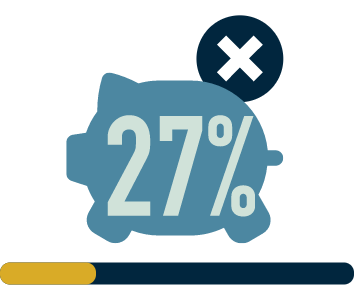

unable to work due to the effects of their disease (n=165)5

(n=136/330) face ≥9 weeks

of sickness absence

from work in the first

2 years after diagnosis6

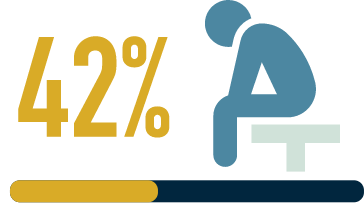

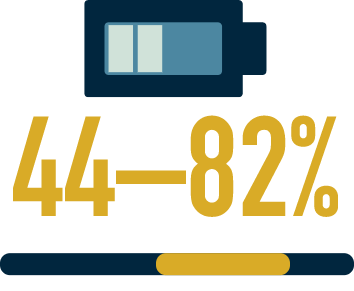

are fatigued7

So may struggle to meet up

with family and friends

So may have a reduced

health-related quality of

life (HRQoL) and increased

burden on caregivers4

So may struggle financially

So may miss out on

work-related opportunities

and progression

So may not be able to plan

for the long term

is a core clinical manifestation

of myasthenia gravis (MG)9 Fatigability is a measurable change in muscle strength over a given time, with symptoms developing or worsening during sustained activity11

In neuromuscular disorders, muscle fatigability is the direct result of the dysfunction of the muscle or the neuromuscular junction (NMJ)8

Understanding of fatigue is limited, but the pathophysiology of fatigue in neuromuscular disorders is believed to have a role in protecting muscles from further damage by downregulating physical activities8,12

- Fatigue may keep individuals from performing daily activities and lower their QoL, which in turn may decrease motivation and further increase fatigue11

- Fatigue can be misinterpreted for laziness in the workplace, which can contribute to the social and professional disadvantages many patients with gMG experience6

Fatigue in MG is associated with higher disease severity,

higher rates of depression, and lower

quality of life8,10

Clinical assessments often exclude fatigue, and studies often use different questionnaires to measure it, but there is a need for consensus and further studies with fatigue as a primary endpoint8,11

The recently developed Myasthenia Gravis Symptoms Patient-Reported Outcome (MGSPRO) scales contain a detailed assessments of muscle weakness (ocular, bulbar and respiratory), muscle weakness fatigability and an assessment of physical fatigue, an aspect not included in other PRO instruments15,16

- Unlike other PRO instruments, the MGSPRO contains a more granular assessment of muscle weakness and muscle weakness fatigability symptoms, and was designed with patient input at every stage

Recent studies used the Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Fatigue (Neuro-QoL Fatigue) subscale to assess fatigue in gMG, and evidence supports the Short Form (SF) as a valid and reliable measure17,18

patient-reported and composite measures of gMG disease severity, including fatigue

| Scale | Measures | For people with gMG, improvement could mean: |

|---|---|---|

| Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL)19 |

Ocular, bulbar, respiratory, motor/limb impairment19 |

Being able to chat with family and friends without the fear of speech becoming garbled |

| Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG)20,21 | Ocular, bulbar, respiratory, muscle strength and fatigability20 |

Better hand grip and leg strength |

| Myasthenia Gravis Composite (MGC)20,21 | Ocular, bulbar, respiratory, limbs, neck | Being able to chew and swallow more confidently |

| Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index (MGII)21,22 | Ocular, bulbar, limb impairment, neck | Reduced fatigability and impairment throughout the day |

| MGSPRO14 | Ocular, bulbar, respiratory, limbs, neck and fatigability |

Having enough energy to last throughout the day |

| Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15-item Scale – Revised (MG-QoL15r)20,21 |

HRQoL as determined by physical, psychological and social aspects of functioning |

Reduced symptom fluctuations, helping work and social life |

| Neuro-QoL-Fatigue-SF11 | General fatigue across 8 patient-reported outcomes |

Having more energy and feeling less tired during the day |

| European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version (EQ-5D-5L)23 |

A generic HRQoL tool across 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression |

Better QoL due to improvement in mobility and ability to complete daily activities |

Efficient and effective communication between

healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients is

critical to optimising the treatment regimen and

driving better outcomes

Long-term planning1

Allowing for more

frequent breaks1

Changing or reducing the amount or type of work they do1

Proactively cancelling plans if necessary1

Adapting the ways in which they conduct activities of daily living, such as eating or personal hygiene1

Patients may be reluctant to report the true impact of their symptoms due to concerns about switching treatment1

People with MG may feel disconnected from their HCP due to limited appointment times, a gap in the perception of disease and treatment burden and differences in treatment goals1

The most suitable treatment may vary for each patient, depending on their individual preferences and circumstances24

Patients with chronic immune system disorders are more likely to choose subcutaneous (SC) administration over intravenous (IV) infusion, but some prefer the IV route24

- The majority of patients prefer SC therapies due to the convenience and independence associated with self-administration at home

- The minority of patients favour IV infusions due to the infrequency of treatment and the feelings of safety due to hospital administration

It is important that the method of treatment administration does not add to the burden of a patient’s disease24

to their healthcare team

*Fatigue with a duration of ≥6 months.8

EQ-5D-5L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version; gMG, generalised myasthenia gravis; HCP, healthcare professional; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IV, intravenous; MG, myasthenia gravis; MG-ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; MGC, Myasthenia Gravis Composite; MGII, Myasthenia Gravis Impairment Index; MGSPRO, Myasthenia Gravis Symptoms Patient-Reported Outcome; MG-QoL15r, Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life 15-item Scale – Revised; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; Neuro-QoL-Fatigue-SF, Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Fatigue short form; PRO, patient-reported outcome; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis; QoL, quality of life; SC, subcutaneous.

References